|

written by Per

Jerberyd

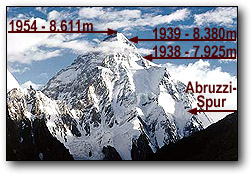

The climbing history of K2, Mount Godwin Austen (8,611 metres),

from the first try in 1902, until the Italian success in 1954.

In 1902, a

six-man group of European climbers, led by the Englishman Eckenstein, headed for K2. They chose the time before

the monsoon. They first crossed the Baltoro glacier, which with

it's length of 67 kilometres is the world's third largest. The

expedition reached the mountain's foot and planned to make the

attempt directly from the south over the Southeast Ridge, but when

in place they came to the conclusion that the Northeast Ridge is

probably much easier. Several attempts were made without success.

They only reached 6,600 metres - this group had an unrealistic

goal, and didn't realise their limits. At this time, early in the

century, they had no idea of the difficulties in ascending such a

high mountain.

Englishman Eckenstein, headed for K2. They chose the time before

the monsoon. They first crossed the Baltoro glacier, which with

it's length of 67 kilometres is the world's third largest. The

expedition reached the mountain's foot and planned to make the

attempt directly from the south over the Southeast Ridge, but when

in place they came to the conclusion that the Northeast Ridge is

probably much easier. Several attempts were made without success.

They only reached 6,600 metres - this group had an unrealistic

goal, and didn't realise their limits. At this time, early in the

century, they had no idea of the difficulties in ascending such a

high mountain.

Seven years

later it was time for the Duke of Abruzzi's large expedition to

Karakorum and K2. Besides the scientific exploration, this royal

adventurer also had plans for alpine operations. K2 was now

scouted closely and the famous mountain photographer  Vittorio

Sella took a lot of fabulous and legendary photos. To start with,

they tried to reach up through the South East Ridge (that later

was named after the Duke). However, the bearers were not trained

for this exposed climbing (The Sherpas were unfortunately

"unknown" during the early part of the century!). Vittorio

Sella took a lot of fabulous and legendary photos. To start with,

they tried to reach up through the South East Ridge (that later

was named after the Duke). However, the bearers were not trained

for this exposed climbing (The Sherpas were unfortunately

"unknown" during the early part of the century!).

Northeast of K2,

some of the expedition members reached the 6,666 metre high Savoia

Saddle and from there they had a closer look at K2's giant

North-Face. Later, the expedition made an attempt to climb K2's

guardian in the west, the 7,544 metre high Skyang Kangri, but a

giant gorge blocked their way at 6,600 metres. However, later on

Chogolisa (7,654 metres) the Duke reached 7,500 metres with a

resolute attack. This became an absolute high altitude record

until 1922 when it was beaten on Everest.

The Italians

now celebrated their 20 year anniversary in Karakorum. This time

the expedition was lead by the Duke of Spoleto, the nephew of the

Duke of Abruzzi. The scientific leader was Professor Ardito Desio

and it is mainly to his credit that the expedition didn't return

home completely without results.

The plan to try climbing K2 was abandoned and it was decided to

concentrate solely upon scientific work in the Baltoro region.

In 1938 it was

time for the next expedition, organised by the American Alpine

Club and led by Charles Houston, who two years previously had been

on the successful expedition to Nanda Devi. They were confident of

succeeding this time too! They engaged a team of excellent Sherpas,

led by the famous Pasang Kikuli. In the beginning of June the

whole expedition reached the mountain.

On July 1, Camp I was established and several others followed. The

weather looked stabile and clear.

On July 18, Houston and Petzoldt reached the "shoulder"

at 7,740 metres and they  succeeded

in conquering the difficulties on the lower part of the mountain ,

the last high altitude camp was established at 7,530 metres. succeeded

in conquering the difficulties on the lower part of the mountain ,

the last high altitude camp was established at 7,530 metres.

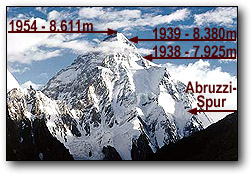

On July 21, Houston and Petzholdt started to push upwards again,

trying to find possible sites for Camp VIII. A place is found

right below the top pyramid. Petzholt however, continued climbing

further on, trying the rocks, his highest point is estimated to be

at 7,925 metres.The sky was clear and the sun warm. Continue or

not? The decision was made and they started the descent. The

expedition results looked promising, for the first time K2's

summit was threatened for real.

Again the

Americans stood in front of K2, this time with the excellent

German-American climber Fritz Wiessner as the leader and again

Pasang Kikuli leading the Sherpas. However, the other climbers

didn't measure up to Wiessner's class, something that would have

serious consequences later on.

Camps I - VII were set up at the same places as the year before

and Camp VIII was established at 7,710 metres, the expedition

member Wolfe remained here when Wiessner and Pasang went on ahead

to set up Camp IX at 7,940 metres. On July 19 Wiessner and Pasang

decided to try for the summit. They climbed through the rocks and

it became extremely arduous. At 6 p.m. they reached about 8,380

metres. Pasang refused to continue, saying it was too late.

Wiessner wanted to continue, the weather was so good and clear

that the climb could be done in the moonlight. Pasang is

immovable, and they start the descent.

During the descent, the rope got stuck in Pasang's crampon and was

torn away from his pack and fell down the abyss. At 2.30 a.m. they

reached Camp IX totally exhausted. Their big chance had slipped

away through their hands; they had been closer to reaching an

8,000-metre summit than anyone before.

The next day, they rested, but the following day another try was

made, taking a different route. Passang had only one crampon.

After major difficulties, they headed back again.

With no supplies remaining the following day, they descended to

camp VIII, where Wolf welcome them with delight, he told them that

during the entire time they were gone, no one had come up from

Camp VII where a bigger supply depot was supposed to be. When  reaching

Camp VII, they found it abandoned. They spent the night there and

the following morning decided that Wolf would remain, while

Wiessner and Pasang continued down to organise a new attack. When

they got to Camp VI it was clear that a catastrophe was near, also

this Camp was abandoned, as were all the other Camps all the way

to Camp II! reaching

Camp VII, they found it abandoned. They spent the night there and

the following morning decided that Wolf would remain, while

Wiessner and Pasang continued down to organise a new attack. When

they got to Camp VI it was clear that a catastrophe was near, also

this Camp was abandoned, as were all the other Camps all the way

to Camp II!

Completely

exhausted both physically and mentally, and suffering from

frostbite, Weissner and Pasang reached Base Camp on July 24. While

they had struggled for the summit, the whole organisation had

completely fallen apart. Against Weissner's orders, the remaining

members of the expedition (that never reached higher then Camp II)

had given the Sherpas orders to abandon all Camps up to number

VII.

Now they had to save Wolfe! After two desperate and failed

attempts, Pasang Kikuli and some other Sherpas managed to reach

Camp VI on July 28. The next morning they got up to Camp VII and

the very exhausted and apathetic Wolfe. Even after being given hot

drinks he couldn't manage to descend immediately, but promised to

be ready the following morning. The Sherpas returned to Camp VI

where they spent the night. A storm with bad weather started to

rage over K2 and they had to wait another day. At dawn on July 31

Pasang and two other Sherpas again climbed to Camp VII while the

fourth, Tsering, remained in camp. A decision was made to somehow

get Wolfe down or at least get a written message from him that

would free them from all responsibility.

This was the last

ever heard from these four men. On August 2, Tsering alone reached

Base Camp and told that none had returned and that no sign of

human life could been seen higher up. Wiesser made a last

desperate rescue attempt but was forced to give up after spending

three days in Camp II waiting out a storm. This meant the end, any

survivor could no longer be found on the mountain. Dudley Wolfe,

Pasang Kikuli, Pasang Kitar and Pintso rest forever on K2. So

ended the second American attempt on K2, with a tragedy. The

expedition got massive criticism from both England and the U.S.A.,

and Wiessner had difficulties defending himself, but he was hardly

the one to blame. Pasang Kikuli was one of the best Sherpas, and

at this time he was equally compared to the now world famous

Tenzing Norgay. More...

|

|

|

Englishman Eckenstein, headed for K2. They chose the time before

the monsoon. They first crossed the Baltoro glacier, which with

it's length of 67 kilometres is the world's third largest. The

expedition reached the mountain's foot and planned to make the

attempt directly from the south over the Southeast Ridge, but when

in place they came to the conclusion that the Northeast Ridge is

probably much easier. Several attempts were made without success.

They only reached 6,600 metres - this group had an unrealistic

goal, and didn't realise their limits. At this time, early in the

century, they had no idea of the difficulties in ascending such a

high mountain.

Englishman Eckenstein, headed for K2. They chose the time before

the monsoon. They first crossed the Baltoro glacier, which with

it's length of 67 kilometres is the world's third largest. The

expedition reached the mountain's foot and planned to make the

attempt directly from the south over the Southeast Ridge, but when

in place they came to the conclusion that the Northeast Ridge is

probably much easier. Several attempts were made without success.

They only reached 6,600 metres - this group had an unrealistic

goal, and didn't realise their limits. At this time, early in the

century, they had no idea of the difficulties in ascending such a

high mountain. Vittorio

Sella took a lot of fabulous and legendary photos. To start with,

they tried to reach up through the South East Ridge (that later

was named after the Duke). However, the bearers were not trained

for this exposed climbing (The Sherpas were unfortunately

"unknown" during the early part of the century!).

Vittorio

Sella took a lot of fabulous and legendary photos. To start with,

they tried to reach up through the South East Ridge (that later

was named after the Duke). However, the bearers were not trained

for this exposed climbing (The Sherpas were unfortunately

"unknown" during the early part of the century!). succeeded

in conquering the difficulties on the lower part of the mountain ,

the last high altitude camp was established at 7,530 metres.

succeeded

in conquering the difficulties on the lower part of the mountain ,

the last high altitude camp was established at 7,530 metres. reaching

Camp VII, they found it abandoned. They spent the night there and

the following morning decided that Wolf would remain, while

Wiessner and Pasang continued down to organise a new attack. When

they got to Camp VI it was clear that a catastrophe was near, also

this Camp was abandoned, as were all the other Camps all the way

to Camp II!

reaching

Camp VII, they found it abandoned. They spent the night there and

the following morning decided that Wolf would remain, while

Wiessner and Pasang continued down to organise a new attack. When

they got to Camp VI it was clear that a catastrophe was near, also

this Camp was abandoned, as were all the other Camps all the way

to Camp II!